“As the human larynx has no other function than to produce a sound with a particular timbre, which is amplified by resonance in the pharyngeal, oral and nasal cavities, and serves, by articulation, for speech, it was clear from the outset that what was needed was simply a device whereby expiration would produce a sound as close as possible to the human speaking voice in pitch and timbre and could then be used for articulation.”

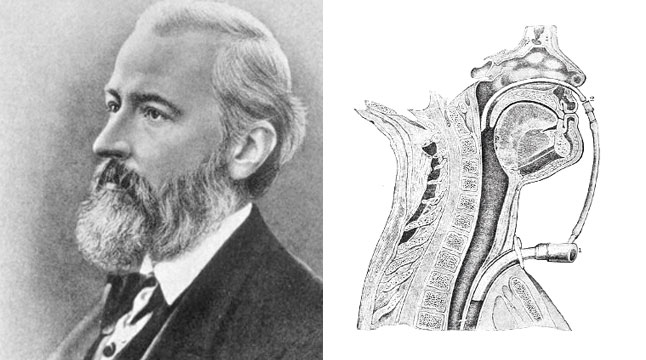

Carl Gussenbauer - 1874

As it happens, it was a tracheotomy that initiated the development of the voice prosthesis. Prague born physiologist Johann Nepomuk Czermak (1828–1873) designed a device that would restore the voice of an 18 year old girl who was tracheotomised for complete laryngeal stenosis. Well known for introducing and improving the laryngoscope into medicine, Czermak adopted the principles of a reed based instrument to enable his device to make sound. The reed itself was metal, much like an accordion or harmonica or the reed pipes of organs. Air expelled from the lungs through the tracheostoma would pass over the reed and cause vibration and thus sound. This was then routed to the mouth where it could be modulated by the vocal tract, as occurs in normal phonation. Czermak’s external device was the forerunner of the voice prostheses.

For the very first internal artificial larynx we would have to wait until Carl Gussenbauer (1842 – 1903) who designed and developed a device that would be used in the first total laryngectomy. This was performed by the renowned German surgeon Christian Albert Theodor Billroth (1829 – 1894) on December 31, 1873. The patient was 36 years old and had a subglottic tumour for which Billroth originally performed a vertical partial laryngectomy (presumably to preserve some laryngeal function). However, the patient’s condition worsened and a total laryngectomy was performed.

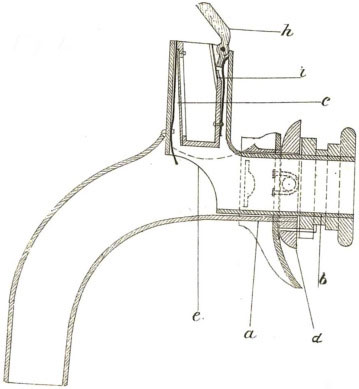

Billroth’s love of music and investigations into the nature of sound, the research of which was published posthumously, may well have played a role in the discussions that I imagine he would have had with Gussenbauer on how to best compensate for the extirpation of their patient’s larynx. At that time Gussenbauer was Billroth’s assistant, a position he held for 6 years until 1875. From Gussenbauer’s report to the Third Congress of the German Surgical Society in Berlin in 1874 we know Billroth had considered an external device that had at time had been developed and tested by Professor Ernst Brucke. However, in the same report Gussenbauer went on to describe the success of his own design and hence its successful use as the first internal artificial larynx. The device had a pharyngeal cannula, complete with mechanical epiglottis, that would pass vibrating air into the vocal tract. Again, a reed was used for sound production, this being located in the “phonation cannnula”. According to Gussenbauer his approach was guided by Vincenz von Czerny, another assistant to Billroth. Czerny had researched and developed an artificial larynx which he evaluated in laryngectomised dogs. The device was a “T” shaped cannula that included, “... a ball valve to block the expiration at the neck and force it to pass through the pharyngeal cavity”.

Gussenbauer’s device achieved its purpose, but certainly had disadvantages. It could not remain in place for long periods, it made breathing difficult and gave the patient a metallic voice. In the context of the late 19th century this was still a success. At least Billroth’s patient had some voice for the 7 months he survived before succumbing to recurrence. A reasonable otucome when you consider that the laryngectomies that followed had a 50% mortality rate. It was not until Themistocles Gluck introduced the two-step laryngectomy in 1881 that mortality improved at least tenfold, Gluck reporting an 8.5% mortality rate. And whilst this article is focussed on pneumatic prostheses, it is worth mentioning that Gluck would go on to develop the first electrolarynx in 1910. This innovative device was comprised of an Edison cylinder phonogram, playing a recording of only one sung note. The sound delivered to the mouth via a telephone receiver could then be phonated by the patient.

Design improvements on Gussenbauer’s device followed rapidly. Notably, in 1877, David Foulis described a similar device that was a somewhat simpler design and integrated sound production inside the tracheal cannula. In this way the voice was less metallic. In 1871 Victor von Bruns (1812 – 1883) introduced a one way valve, at the tracheostoma, that meant patients did not have to manually occlude the opening on expiration. He also introduced a rubber reed to generate a more natural sounding voice. More improvements followed with Paul von Bruns (Victor’s son) and Julius Wolf making significant contributions that would bring better sound and also ease of fitting and use.

Improvements to voice prostheses continued until a pivotal moment in 1972 when Polish otolaryngologist Erwin Mozolewski (1917–2007) described an internal voice prosthesis (arytenoid vocal shunt) that he had implanted into 24 laryngectomised patients. Mozolewski designed and manufactured from poly-vinyl-chloride or poly-ethylene a one-way tubular valve, the basic idea of which is still in use today. An improved version of this shunt was introduced by Blom and Singer in 1979. These silicone prostheses were design to be inserted into a surgically created tracheo-oesophageal puncture (TEP), or fistula, a surgical technique which in itself was a major breakthrough. Unlike earlier pneumatic voice prostheses the tracheo-oesphageal (TE) valve did not implicitly generate a sound. It relied on the redirection of airflow provided by pulmonary exhalation into the oesophagus, inducing vibrations in the pharyngo-oesphageal segment. These simple one way valves that appear to be no more than a tube and some flanges are in wide use today. There are two differnt TE valve tyeps, the indwelling an non-indwelling. So if a patient prefers they can elect to have the non-indwelling type which allows them to remove and refit the device, whereas the indwelling type needs to be fitted by a healthcare professional. Indwelling TE valves will last longer and require less maintenance. Either type allows the patient to control airflow and pressure, giving for a more natural and fluent voice compared to any other currently available voice prosthesis.

This outline from the early attempts to produce an artificial voice tells us that voice rehabilitation was never an afterthought. From the first laryngectomy on it has always been integral to treatment, and so it remains. From clunky metal cannulas analgous to musical intruments to tiny silicone devices, the journey to give patients back their voice with the least discomfort and the greatest audio fidelity continues, but it certainly has come a long way.